Midway through the first season of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why, lead character Clay (Dylan Minnette) chats with his dad about why Clay is depressed and behaving strangely. Mr. Jensen (Josh Hamilton) confides in his teenage son that he hated high school. He was bullied, he admits, but he assures his son that he survived, intimating that Clay too will survive. If we consider this brief exchange within the history of media about teens, it’s an interesting and relatively bold one: film and television adults might admit to having had “a hard time” as teens, but rarely have they been allowed to talk about actively “hating” high school. And yet within the episode, the exchange is even darker, even less hopeful, since 13 Reasons Why explores why one of Clay’s best friends committed suicide, so we know that Mr. Jensen’s implied moral is wrong – not everyone does survive high school.

In striking such a tone, 13 Reasons Why joins American Crime’s second season and the Netflix documentary Audrie and Daisy (both 2016 Peabody finalists, Audrie and Daisy a Peabody winner) in offering a more challenging, less effervescently nostalgic depiction of teen life than has been Hollywood’s norm. Each begins with a suicide and/or a rape. Each shows us pain – not just “angst” – that cannot be overcome. Each powerfully shows how social media has transformed the experience of being a teen: like Mr. Jensen, the adults among us may feel we’ve been there and lived that too, but all three programs disallow that easy sentiment of identification. Bullying, depression, and trauma are not new experiences for teenagers – plenty of people for plenty of generations have joined Mr. Jensen in hating high school – but these three shows should challenge us both to consider how social media amplifies their damage, and to address each as serious problems, not just perennial burs in teenagers’ socks.

In suggesting that these shows’ takes on teenage life are relatively novel, I do not mean to suggest that film and television have shown us only happy images of teens easily dancing their way through high school to the beat of various period-appropriate pop songs. Admittedly, many depictions of teenage life are heavily invested in nostalgia, offering us paeans to young love, and to becoming a man or (less often) woman. Saved By the Bell, for instance, never met a teen problem it couldn’t solve in 22 minutes, and thereby toed the line of countless teen shows that came before it, while laying down a baseline for many that followed it. John Hughes’ films, meanwhile, regularly gestured to the weight of social expectations, before shaking them off to get back to the fun.

So common, in fact, have been the more upbeat depictions of teen life that they made of themselves an easy target for more satiric engagements. Not Another Teen Movie and Mean Girls stand out as parodic-satiric attacks on both how film and television have depicted high school, and the vicissitudes of teenage life in general. Multiple teen dramas on television, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to many CW shows (most recently, Riverdale), have shown less satirical impulse, but have regularly been bold in painting teen life as sometimes dangerous and scarring, not just taxing. Thus, American Crime’s second season, Audrie and Daisy, and 13 Reasons Why do not reach us entirely as lightning out of clear sky.

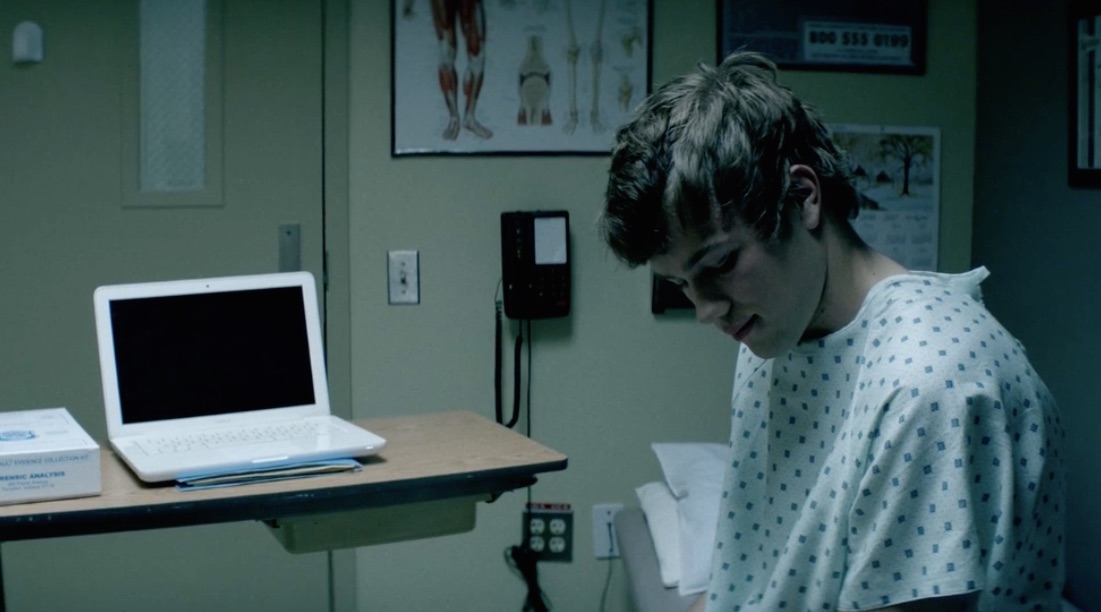

Nevertheless, all three draw both the camera and the mic closer to teen pain. Indeed, all three use form to offer viewers a portal into the interior space of suffering teens. American Crime makes regular use of close-ups, at times allowing the camera to ignore other characters so that instead we stay with the teens in question. Thus, for instance, when Taylor’s mother takes him to the hospital to report his rape, we never see his nurse, only hearing her questions as instead we suffer the stings of each probing question with Taylor (Connor Jessup. See image below). Audrie and Daisy, meanwhile, stops to look inside Daisy Coleman’s sketch book at the disturbing images she draws to communicate her pain. And 13 Reasons Why takes the form of one long diary-meets-suicide-note, as Hannah Baker (Katherine Langford) explains why she killed herself to Clay and to us. 13 Reasons Why also regularly enacts Clay’s hallucinations, memories, and fantasies, thereby giving viewers an intimate attachment to him and his feelings.

The shows do not hide from all sorts of other signs of teens suffering trauma. Daisy tells us about her self-harm, and we see another character in 13 Reasons Why with scarred arms. Clay has a history of nightmares while another friend has stress-induced stomach pains. Taylor’s alleged assailant Eric (Joey Pollari) is abandoned by his mother, who cannot accept that he is gay. Audrie and Daisy’s titular characters are hounded on social media, and the documentarians recreate Facebook posts to offer us the experience of seeing taunts, shaming, and innuendo popping up and proliferating in real time.

They work against teen show conventions in other ways too. We’re used to high school being colorful, especially since film and television have suggested that half of all high schools in the US are bathed in Southern California’s warm sun. American Crime and 13 Reasons Why regularly offer us scenes dipped in pale, lifeless blues, while Audrie and Daisy’s documentary style looks thousands of miles from The OC (even while beginning in California with a blond surfer).

Elsewhere in film and television, high school is also regularly a site of overloaded screen erotics – everyone has crushes that crackle with energy, most characters are either dreaming of having sex, actually having sex, or debriefing sex. Most of the sex in these three shows, though, is nonconsensual and hence violent and destructive. The closest the narrator in 13 Reasons Why gets to caring, consensual sex is ended abruptly when her memories and experience of sexual violence render the act repulsive to her. Even making out is fraught, often motivated by one person wanting to manipulate someone else, often surveilled. American Crime begins with audio of Taylor’s mother reporting her son’s rape, then juxtaposes this with visuals of a young man being pushed with increasing force, thereby establishing touch as always potentially violent. And with this differing attitude towards adolescent sex, sexiness changes too, as the shows understandably back away from presenting a parade of young bodies on display for viewers. They’re not prudes about sex, and they avoid a patronizing message of abstinence, but they refreshingly refrain from turning teen life into a spectacle of erotic energy.

Just as the sexual energy of the teen show is frustrated, therefore, so too is the nostalgic impulse. If nostalgia is “memory without pain,” a scrubbing up and prettification of our past, American Crime’s second season, Audrie and Daisy, and 13 Reasons Why resist their genre’s fondness of nostalgia. 13 Reasons Why plays an interesting game with nostalgia, though, placing Hannah’s suicide “note” across 7 cassette tapes that therefore require listening to via cassette player. Brief nostalgia ensues, complete with jokes about Clay’s unfamiliarity with the term “boom box,” and Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” But the nostalgia is a trap, for once we put on the Walkman with Clay, we go not backwards to a nostalgic past, but stay in the present, hearing a story that regularly involves private photos taken on a cell-phone and shared with the school.

I don’t see an “attack” on social media and cell phones, to be clear (and as much as Audrie and Daisy’s poster, above, suggests). These are not episodes of Black Mirror showing us a horrific future of unchecked swipe-left iPower. Indeed, in both of the fictional shows, characters are also able to reach out for help and friendship via cell phones at key moments. If the three share a message about social media and cell phones, therefore, it’s an insistence that they’ve changed what social pressure, judgment, and visibility mean for teenagers. Teens have long been an odd breed for caring intensely and too much what the world thinks at one moment, forgetting that they exist at the next. And almost every film or television tale about high school has at some level been a tale about cliques and belonging, sometimes focusing in more upbeat style on friendship and community, sometimes more pessimistically on the possibilities for exclusion and isolation. But these three programs tell us that the terms of engagement have changed. Exclusion and isolation don’t just happen in the cafeteria while looking for a table, and cliques don’t just determine who is invited to the party or not. The social policing, surveillance, judgment, and pressures of social media can follow teens everywhere.

Admittedly, 13 Reasons Why struggles under the weight of its gimmicky premise – one tape per episode, each about another person who led to Hannah’s suicide. I found myself incredulous that Clay wouldn’t simply listen to all the tapes at once. At those and other moments, the artifice of the tale showed too nakedly. 13 Reasons Why also exists in a naively post-prejudiced world in which one character can allude in passing to being teased because he’s gay, yet the rest of the show suggests that the high school has transcended homophobia and racism. By contrast, American Crime is far more careful to show how race, sexuality, and gender matter. It deftly manages to show both how some teens are struggling with way more, while acknowledging that nobody has it “easy” per se. And yet all three shows are primarily about whiteness, all relying a little too much on the threat to beautiful white people as narrative engines. None should be damned for this, but all could be better.

Ultimately, though, 13 Reasons Why, American Crime’s second season, and Audrie and Daisy perform one of the most important services that media can perform, encouraging empathy. When directed at or available to adults, a lot of teen media have offered themselves up as virtual playgrounds for vicarious, nostalgic pleasures. The better shows and films have often excelled either at reminding us of our own experiences of high school – offering a space for reflection on the decisions we made at the time – or at creating a magical alternative, and a world in which I did ask my crush out, and she said yes. Many of these tales are about us as adults, therefore, not about the teens. Their popularity suggests the degree to which we want, perhaps even need, stories about teens to do this. But these three programs are decisively about teens today, not about how we were teens yesterday.

It is easy to roll our eyes as we see and hear teens bumbling through public space, betraying a performative theatricality (whether of bravado or emo nobody-loves-me-ness) with each loud, grammatically incorrect statement. It’s clearly too easy, as young people are so often focal points for resentment and petty angers. “Kids these days.” It’s also easy, therefore, not to have compassion, and instead to believe that we all had to suffer those years, so it’s this batch’s turn now, and the pain will only make them stronger. It’s harder to empathize, especially since true empathy would require us to tackle hard issues about how to improve the life of teenagers. We’d need to address toxic masculinity head on. We’d need to approach bullying as something more than a slight inconvenience. We’d need to think substantively about how to create a better world for kids and teens with all the power we as adults have, and not just blame them for not changing that world with the very little power they have. 13 Reasons Why, season 2 of American Crime, and Audrie and Daisy all begin that process of creating empathy. Each made me angry and upset, and whereas teen media often makes we wish for something better from my past, these programs make me wish for something better for my child’s and other people’s children’s future. They don’t walk us by the hand and tell us exactly what to do to get there, since that is not their job, but they offer a notable public service nonetheless in asking viewers to care about that journey in the first place.