A great pleasure of parenting for me has been the ability either to return consciously and eagerly to kids’ media and culture that I always loved but was driven away from by age (being able to go into toy stores without looking like a creeper is an especially big plus), or to rediscover things I once loved but forgot. And thus when I started to get my daughter books, I enjoyed the chance to revisit old favorites, from the more obvious (Eric Carle, Dr. Seuss, Beatrix Potter, Where the Wild Things Are, Quentin Blake, Richard Scarry) to more personal favorites (Munsch’s lesser-known Jonathan Cleaned Up – Then He Heard a Sound, or Blackberry Subway Jam or Marriott Edgar’s British seaside tale, The Lion and Albert). But it’s also been wonderful to discover new favorites who weren’t around “in my day.” At the top of that list is Oliver Jeffers.

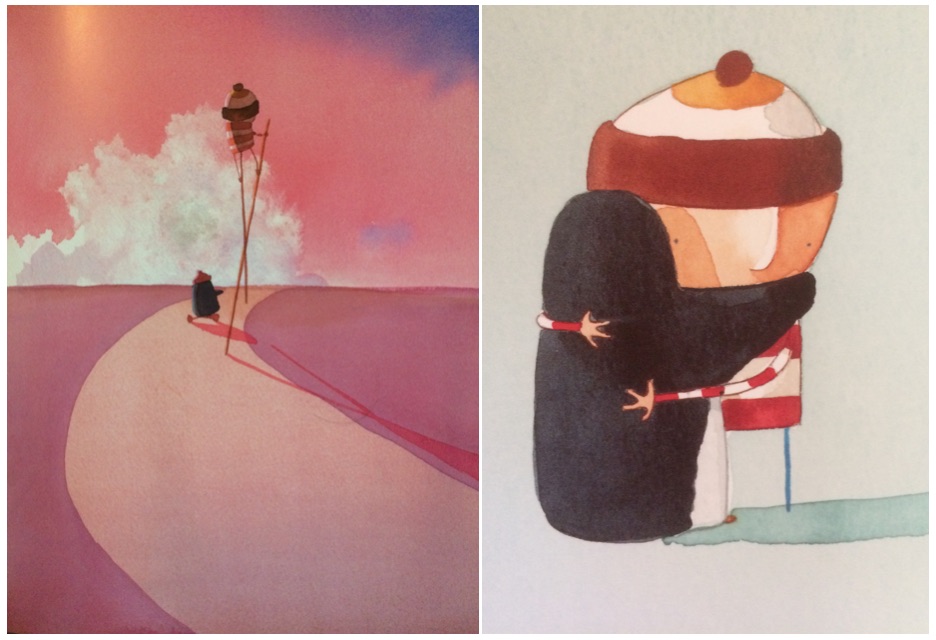

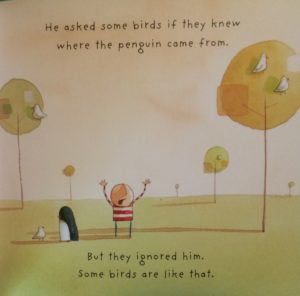

I first encountered Jeffers through his Lost and Found, a sweet story about a little boy who finds a sad-looking penguin at his door. He’s convinced the penguin is lost, and sets about getting him back home, rowing him to the South Pole. After depositing the speechless bird, the boy heads home, only to realize to his horror that the penguin wasn’t lost – it was just lonely and it wanted a friend. Luckily, they reunite. I fell in love with the simplicity and economy of Jeffers’ style as both writer and illustrator. He allows a lot of room for readers to fill in details without lazily requiring them to fill in too much. He mixes whimsy with a sense of magic, and uses a sense of humor that never excludes the child but can offer some extra absurdist points for adults.

I first encountered Jeffers through his Lost and Found, a sweet story about a little boy who finds a sad-looking penguin at his door. He’s convinced the penguin is lost, and sets about getting him back home, rowing him to the South Pole. After depositing the speechless bird, the boy heads home, only to realize to his horror that the penguin wasn’t lost – it was just lonely and it wanted a friend. Luckily, they reunite. I fell in love with the simplicity and economy of Jeffers’ style as both writer and illustrator. He allows a lot of room for readers to fill in details without lazily requiring them to fill in too much. He mixes whimsy with a sense of magic, and uses a sense of humor that never excludes the child but can offer some extra absurdist points for adults.

The book offers a nice lesson about being attentive to loneliness and about caring, that isn’t presented as a reprimand even when the boy got it wrong. Incidentally, there’s also an excellent, super-chill animated short film (great for mornings when you’re tired and need a video to be the parent) that’s charming, and that underlines how Jeffers’ narratives always seem to have one foot already in dreamland.

And so I set off in search of more, and found a whole series (three of which you can get in a “Once There Was a Boy…” box set, with these first three) based around this nameless boy. In The Way Back Home, he finds an airplane in his closet (as one does!) and flies it to the moon, but not before running out of fuel. Along comes a Martian who similarly has engine troubles, so the two unite and hatch a plan to save each of them. In How to Catch a Star, the boy wants to catch a star, and (despite being stymied by yet another recalcitrant bird) eventually succeeds. Or in Up and Down, the boy and his penguin return, with the singular mission to help the penguin live up to his bird legacy and …

And so I set off in search of more, and found a whole series (three of which you can get in a “Once There Was a Boy…” box set, with these first three) based around this nameless boy. In The Way Back Home, he finds an airplane in his closet (as one does!) and flies it to the moon, but not before running out of fuel. Along comes a Martian who similarly has engine troubles, so the two unite and hatch a plan to save each of them. In How to Catch a Star, the boy wants to catch a star, and (despite being stymied by yet another recalcitrant bird) eventually succeeds. Or in Up and Down, the boy and his penguin return, with the singular mission to help the penguin live up to his bird legacy and …

But, as you well know, penguins can’t fly, so ultimately it becomes a nice tale about helping a friend, being there for them as they try, and comforting them if they fail. As with Lost and Found, all of these have charming messages about friendship, being kind, being decent, and yet they’re all in an evocative world of magic, possibility, and absurdity. Jeffers also has wonderful writing – as in the font / script – which feels more child-like and is fitting for a writer who so warmly seems to write from within a child’s world of wonder, curiosity, and need to figure things out (whether laws of physics or social cues).

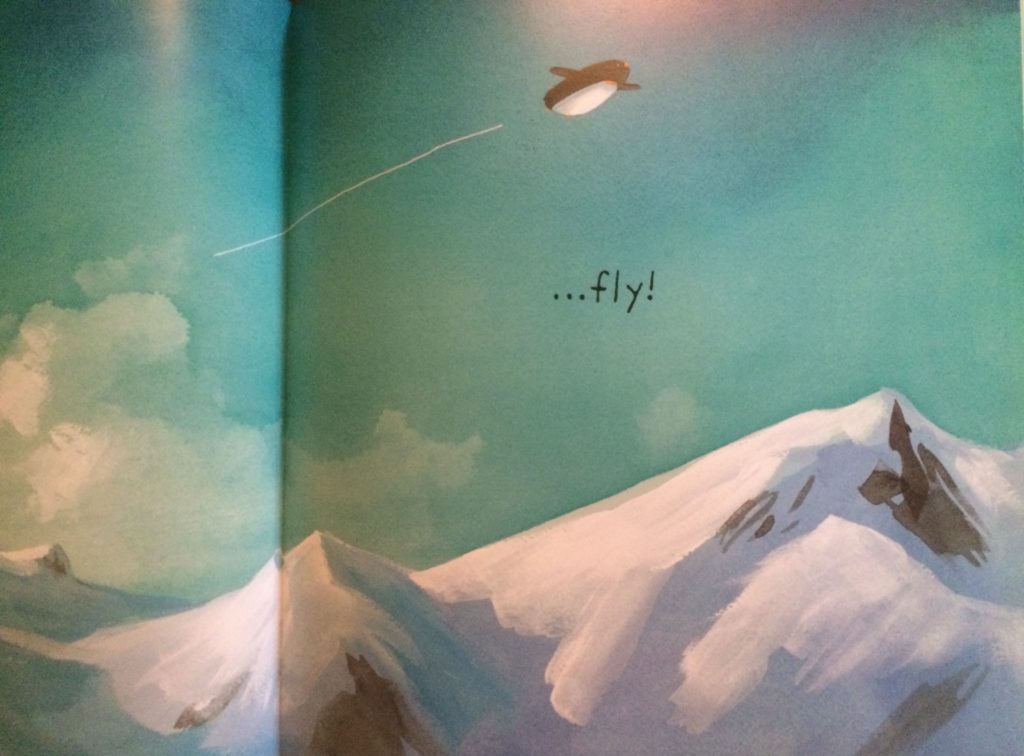

Jeffers is probably most famous, though, for his illustrations of Drew Daywalt’s The Day the Crayons Quit, and its sequel The Day the Crayons Came Home. The concept for the former is simple – young Duncan receives a stack of letters from his crayons, airing their grievances. Each double page offers a different letter, with Black, for instance, upset that it’s only ever the outline of things, Yellow and Orange pleading their case against one another to be made the sole crayon used for coloring in the sun, Blue asking for a break since Duncan over-uses it (as his favorite color), and Peach expressing embarrassment at being naked after Duncan peeled off its wrapper. The sequel then sees a new stack of letters from Duncan’s forgotten and afflicted crayons. For instance, Yellow and Orange return, their love of the sun having led to dire consequences when they melted into one another; the Glow-in-the-Dark crayon writes scared from the basement where Duncan left him; and my personal favorite is the Pea Green crayon who decided that he’s too boring a color so he’s off to see the world (until it rains, that is), and is now to be called Esteban the Magnificent.

The concept is fun, the range of grievances amusing, but Jeffers really makes the books come alive with his personified crayons, his kids’ drawings, and with crayonic writing that once more sets the action firmly inside a kid’s world. As an aside, my daughter learned to read cursive through the first book, but she also adores the characters.

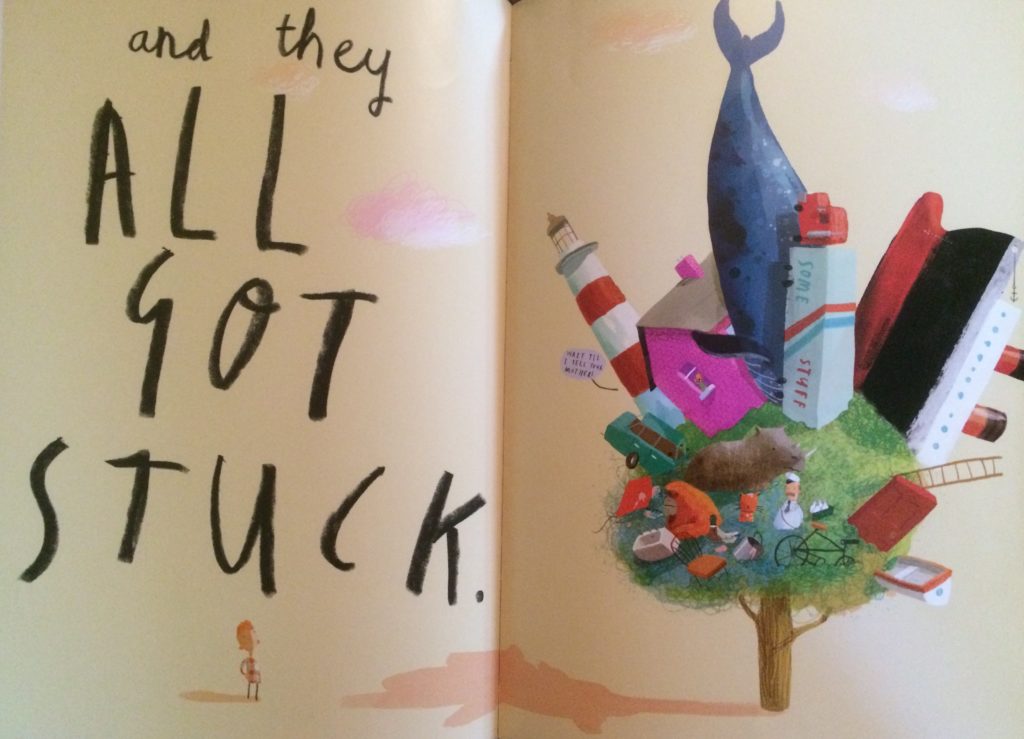

Another really fun Jeffers book comes in the form of Stuck, about a boy whose kite gets stuck in a tree. He tries to get it out by throwing his shoe, but that gets stuck. Then his other shoe, but that gets stuck. Then everything from a firetruck to a blue whale. No great message, just a lot of fun and silliness.

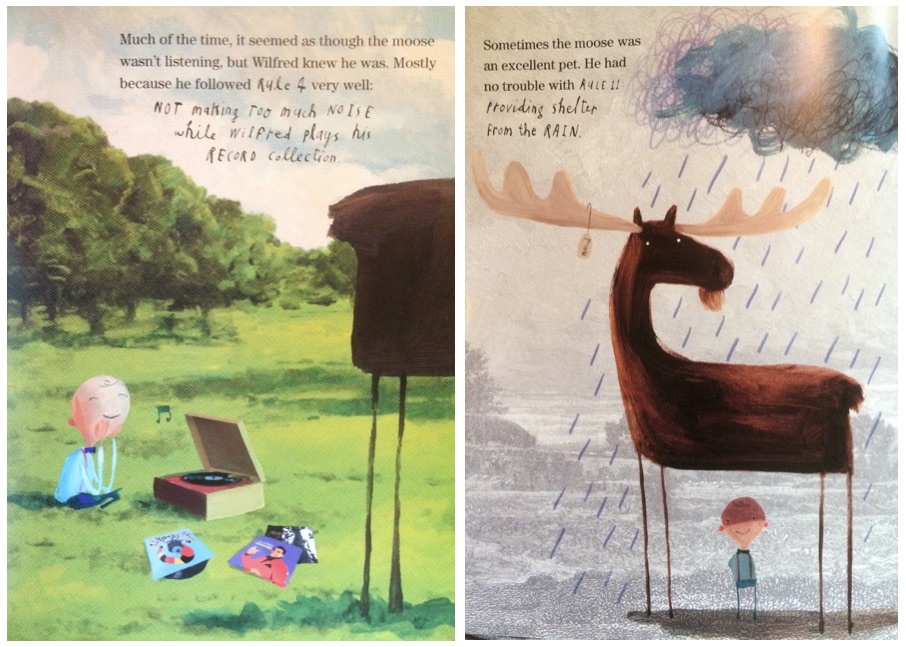

Also delightful is This Moose Belongs to Me, about a boy who discovers his pet moose has other people who seem to think the moose is theirs. As with Stuck, it’s pre-eminently silly. My daughter adores when I say things that are deliberately wrong, so that she can correct me, and I remember my Mum was similarly fond of this technique. It’s nice when kids get to break from being told what’s wrong and right, normal or not, and instead are given the chance both to see a carnival of silliness that gleefully violates some of those rules, and thereby to be able to point out wrong and right themselves. And while at first I think my daughter took the nature of the boy-moose relationship at face value, she’s increasingly enjoyed the ability to laugh at and correct the assumptions this little boy makes about “his” moose’s behavior.

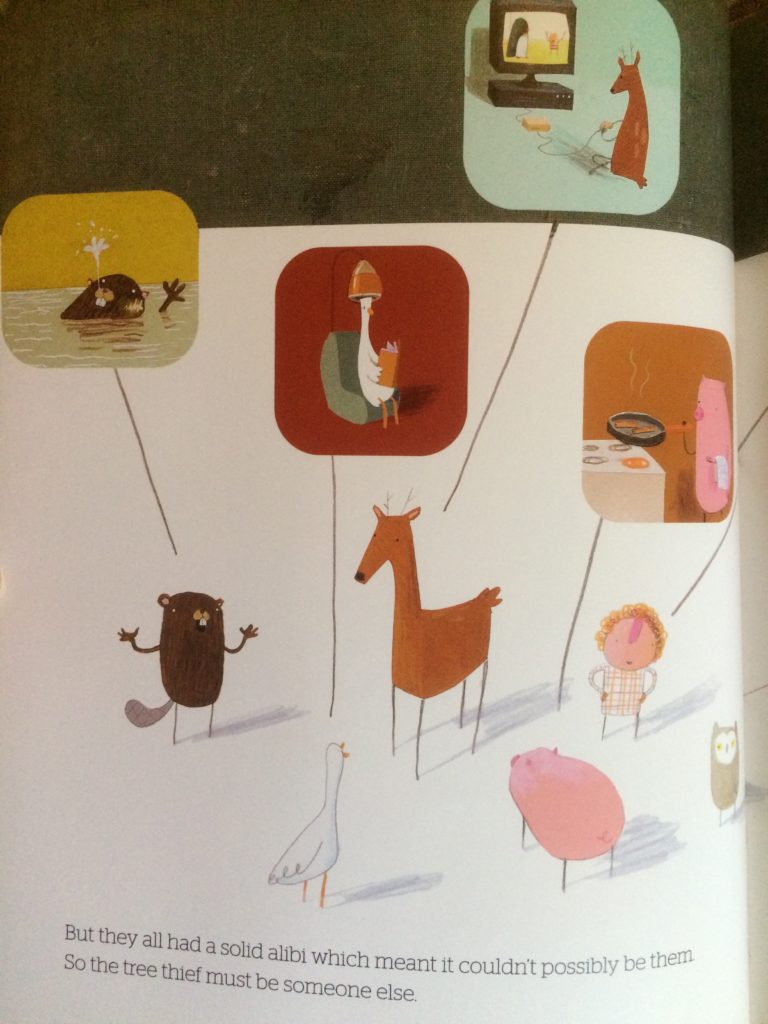

Operating in a similar vein is The Great Paper Caper, about a group of woodland animals who notice their trees are being cut down. They blame each other, and must each provide amusing alibis (see below), even while we see who the culprit is in many frames, thereby allowing the attentive reader to point out what the animals don’t yet know, and to enjoy the feeling of being ahead of the curve. The reader also learns not to jump to conclusions, and to extend some empathy to people who make bad decisions, realizing there may be more to the picture.

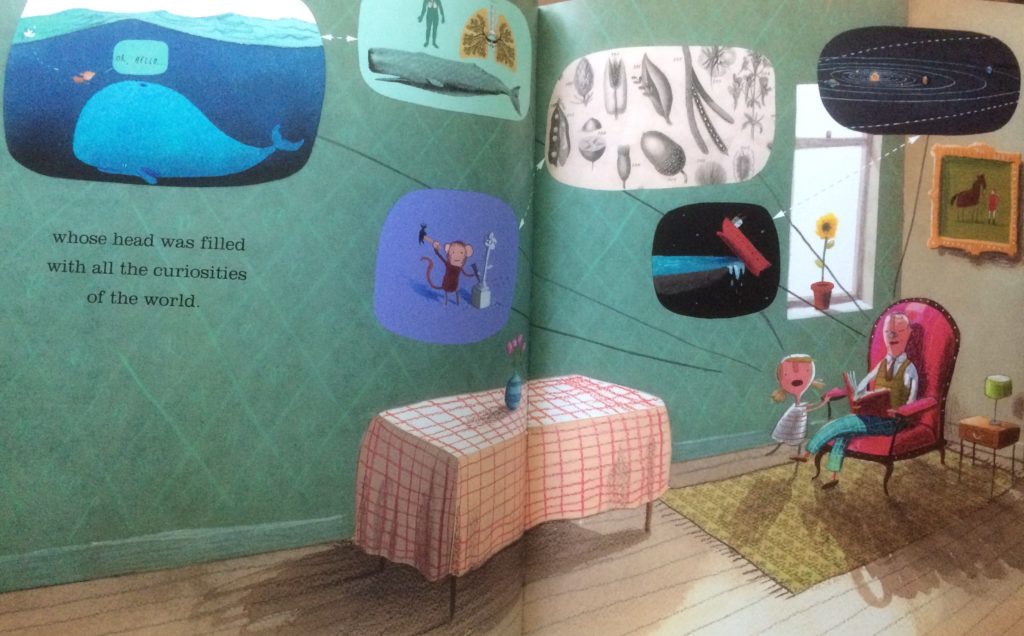

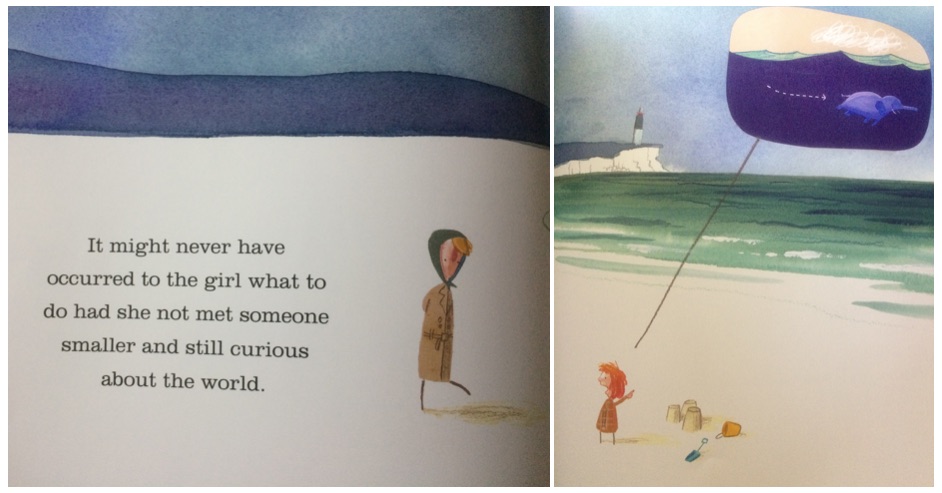

A touching entry in Jeffers’ oeuvre comes in the form of The Heart and the Bottle. This time, our protagonist is a little girl, who adores exploring the world with her grandfather. Jeffers does this neatly evocative thing in some of his books where speech bubbles contain pictures, and The Heart and the Bottle has particular fun with this technique, showing all the many things in the great wide world that this little girl and her grandfather talk about, and explore, imagine, and learn together. The opening pages are beautiful – I really want to frame some, for me even if not for my daughter. And they’re a lovely testament to the imagination and to learning.

But then the little girl finds an empty chair where her grandfather could usually be found. The word “death” is never uttered, but clearly this is what’s happened. The event hardens the girl, who therefore places her heart in a bottle, to protect it from being hurt, but at the cost of being able to use it and to feel it. Until, as a grown woman, she meets another little girl and realizes it’s time to have a heart again.

The Heart and the Bottle gives Robert Munsch’s I Love You Forever a good run for its money in the competition of Kids Story Most Likely to Make Me Cry Every Time I Read It. I already adored it for the first few pages, but its message about dealing with pain and loss is surprisingly honest for a kids’ book – there’s no weird fiction about where grandpa has gone, no quick recovery, just a long process of coming to terms, with a message that we have to keep loving and caring and dreaming. All of this sounds so hokey when I write it, but it encapsulates something I love about great kids’ stories, when they allow and invite me to lie outside at night with the little girl and her grandpa and stargaze alongside them with wide eyes. I’m a cynic who needs and wants to believe in better things, and books like this serve that purpose, as I hope they do to my daughter.

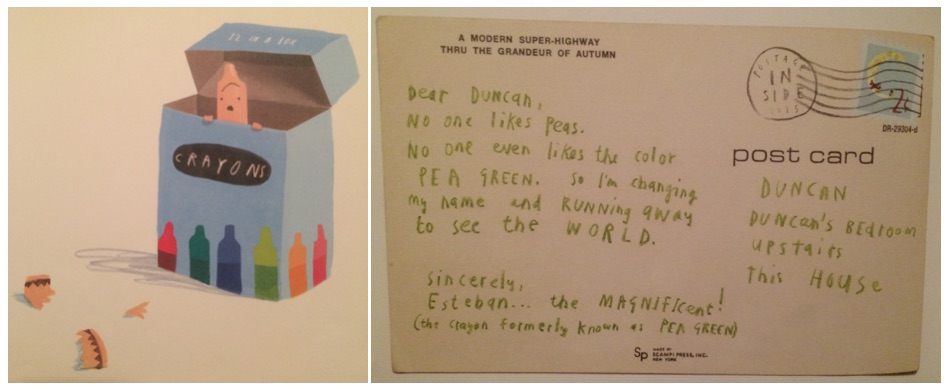

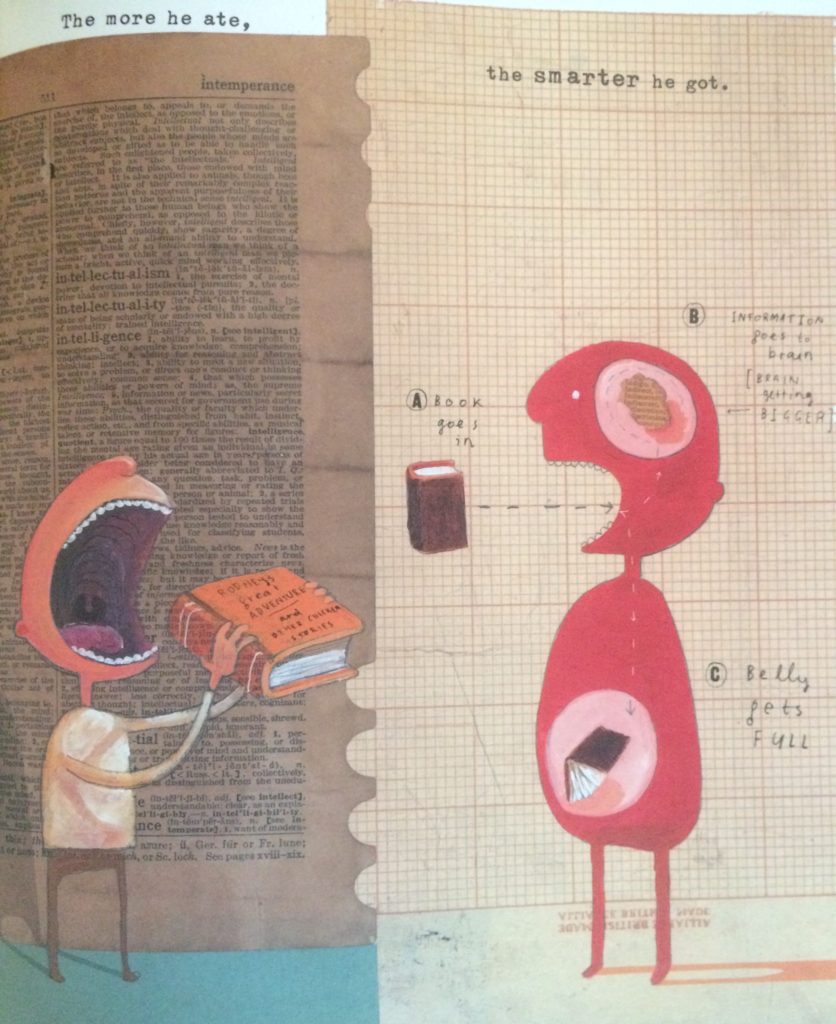

Next to the crayon books, my daughter’s favorite Jeffers, though, is The Incredible Book Eating Boy. This is the tale of a boy who discovers that when he eats books, he gains the information and intelligence therein.

It offers a lovely (if slightly techno-averse) metaphor about what it means to be smart, and about technology and other short cuts’ ways of getting there. Alas for the poor boy, though, he starts eating too much and his brain short-circuits, thus requiring him to go cold turkey and give up book eating in favor of broccoli. He learns to read again, though, and now gets his information slower than before, but still loves reading. It’s a great book-lover’s book, complete with chomp marks in the book itself.

Jeffers has other books – the Hueys series, Once Upon an Alphabet: Short Stories for All the Letters, Imaginary Fred, and A Child of Books (another great book-lover’s book) – but the above provides a tour through some of my favorites. They’re fun, full of imagination, utterly silly and absurd, and yet often starkly beautiful, artistically rendered, and moving. My daughter loved having them read to her, I loved reading them again and again, and now that she’s reading herself, I regularly find them on her bed in the morning, in a pile of books she woke up early to read.